by Christiana Lilly

An opulent manse in Miami, James Deering’s Vizcaya has played host to many a wedding, elaborate engagement shoot, and field trips of schoolchildren learning about Miami’s past. But it also played a prominent role in local LGBT society as the setting for the White Party from 1985 to 2010 and then again in 2018.

But does its gay history go back further?

In short, the answer is “perhaps,” but Julio Capó, an associate professor of history at Florida International University and the author of “Welcome to Fairyland,” has been the foremost expert on our region’s LGBT history.

“I was really interested in learning more about how differently LGBTQ history would look like if we hadn’t censored the voices of mostly Black and brown people who had otherwise often been left out of the general narrative of LGBTQ history,” Capó said.

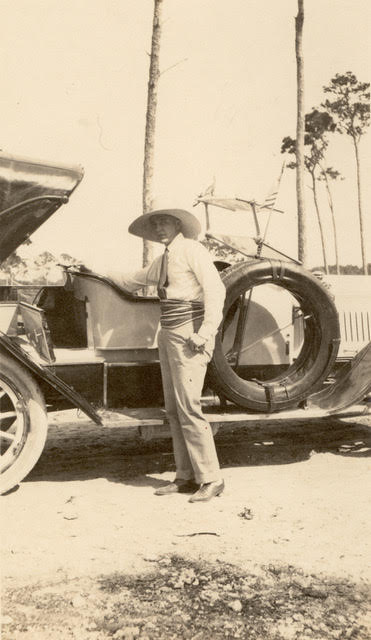

His research took him to Vizcaya when he was studying the Black Bahamian laborers who built the estate. Deering, an agricultural tycoon, began work on the sprawling property in 1912. He moved in four years later, but even at his death in 1925, the home was not complete.

According to Capó’s writings in “LGBTQ America” for the National Park Service, as Vizcaya is a National Historic Landmark, people have long wondered about Deering’s sexuality and if his luxurious home was party central for gay men.

“Vizcaya has been the site of a lot of interest in terms of LGBTQ history,” Capó said. “But a lot of it is unsubstantiated. There’s been all these kinds of rumors of James Deering and his potential sexual appetite.”

The historian pored through records and memorabilia from Vizcaya, but he was not able to find any concrete evidence that Deering was actually gay. However, there were insinuations that seem to keep the rumors going. He was referred to as a “bachelor,” and Capó also found a 1961 newspaper story that went as far as to describe him as a “prissy bachelor who preferred bourbon to women.” It also states that he “staged wild parties” at the home.

In his research, Capó has since reframed the question from, “Is James Deering gay?” to “Why are we asking this question in the first place?”

“Some people commented about his sexual behaviors and preferences during his lifetime and after, and some things are just unanswerable,” he said. “A lot of people just didn’t fit the mold, of the expectations of masculinity, especially for white masculinity for this period, and words like ‘eccentric’ and ‘bachelor,’ these are often coded words.”

However, there is evidence that those in Deering’s circle were gay, including Paul Chalfin, who served as the interior decorater and an architect for the home. According to Capó, he lived openly with his partner, Louis Koons, into the early 1920 — far from the norm at that time. In fact, the late Florida journalist, naturalist and feminist Marjory Stoneman Douglas has written about seeing the two attending a party as a couple.

Capó notes an important fact about Chalfin and others in Deering’s circle: being white and wealthy, they had the privilege to live more openly than perhaps the Black Bahamian men who built the mansion on their backs.

“He was such an important part of Vizcaya’s image and as far as the record shows, lived fairly openly. Almost as an open secret,” he said. “It was kind of understood many ways, and in other ways, celebrated or tolerated in some circles.”

For decades, the queerness of Vizcaya simply lived in the rumors and memories of those who believed Deering to be a forever bachelor because he was gay.

Then, in 1985, the home returned to the LGBT spotlight when it served as the location for the inaugural White Party, the signature fundraiser for HIV/AIDS healthcare organization Care Resource, then known as the Health Crisis Network. It was hosted there until 2010, and then again in 2018.

“People suddenly kind of reimagined or created new memories of Vizcaya with very little evidence for it,” Capó said, a sort of mirage of raucous Saturnalia parties at the level of Jay Gatsby with throngs of gay men in attendance.

Capó does remind us that being gay in the early 20th century would not have been the same as it is today. Queer culture in Miami was limited and “very few people understood themselves primarily through their sexual identity in the way that we think of today.”

“Who knows if James Deering did have same-sex loving affinities, and again I could find no clear evidence of it at all, nor was I looking for it.”